Four new studies from the Wooster Tree Ring Lab have recently appeared in Ecology, Journal of Geophysical Research – Biosciences, The Holoceneand Chemosphere.

Brian Buma lead the study published in Ecologythat described the results of revisiting a classic ecological succession site in Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve. The article is titled: 100 years of primary succession highlights stochasticity and competition driving community establishment and stability. We blogged about some of the fieldwork for this study a few years ago here.

Abstract: The study of community succession is one of the oldest pursuits in ecology. Challenges remain in terms of evaluating the predictability of succession and the reliability of the chronosequence methods typically used to study community development. The research of William S. Cooper in Glacier Bay National Park is an early and well‐known example of successional ecology that provides a long‐term observational dataset to test hypotheses derived from space‐for‐time substitutions. It also provides a unique opportunity to explore the importance of historical contingencies and as an example of a revitalized historical study system. We test the textbook successional trajectory in Glacier Bay and evaluate long‐term plant community development via primary succession through extensive fieldwork, remote sensing, dendrochronological methods, and newly discovered data that fills in data gaps (1940’s to late 1980’s) in continuous measurement over 100+ years. To date, Cooper’s quadrats do not support the classic facilitation model of succession in which a sequence of species interacts to form predictable successional trajectories. Rather, stochastic early community assembly and subsequent inhibition have dominated; most species arrived shortly after deglaciation and have remained stable for 50+ years. Chronosequence studies assuming prior composition are thus questionable, as no predictable species sequence or timeline was observed. This underscores the significance of assumptions about early conditions in chronosequences and the need to defend such assumptions. Furthermore, this work brings a classic study system in ecology up to date via a plot size expansion, new baseline biogeochemical data, and spatial mapping for future researchers for its second century of observation.

Photo taken in the West Arm of Glacier Bay close to where the Cooper plots were “rediscovered” by Buma and others.

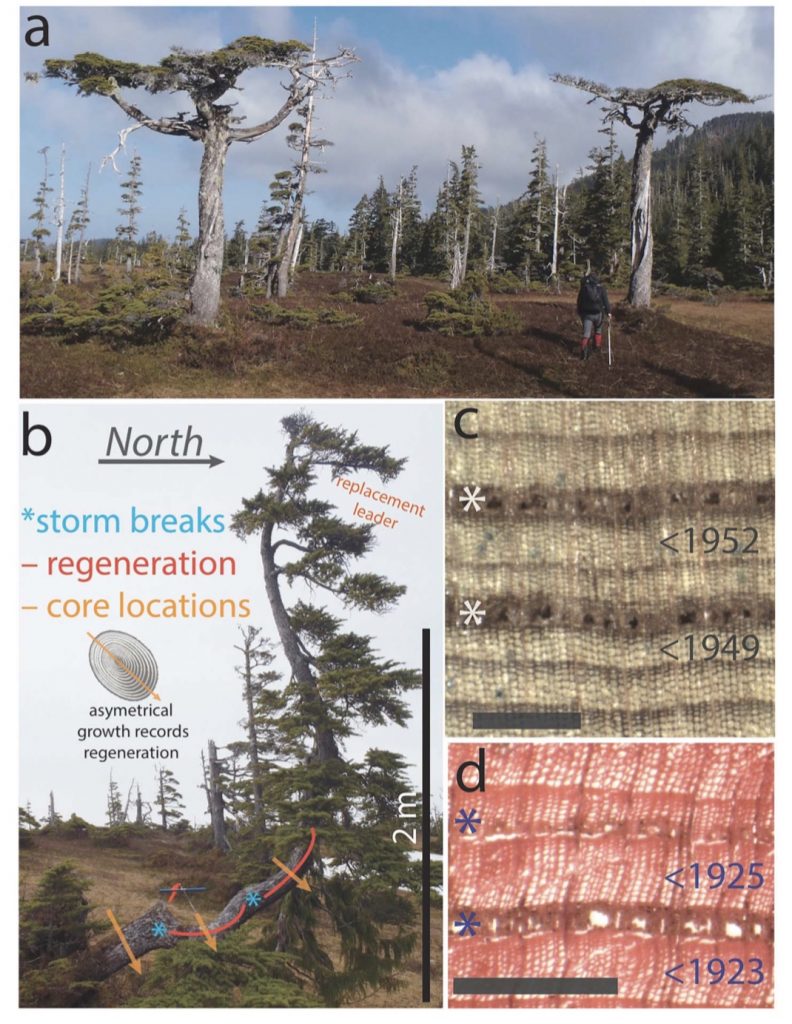

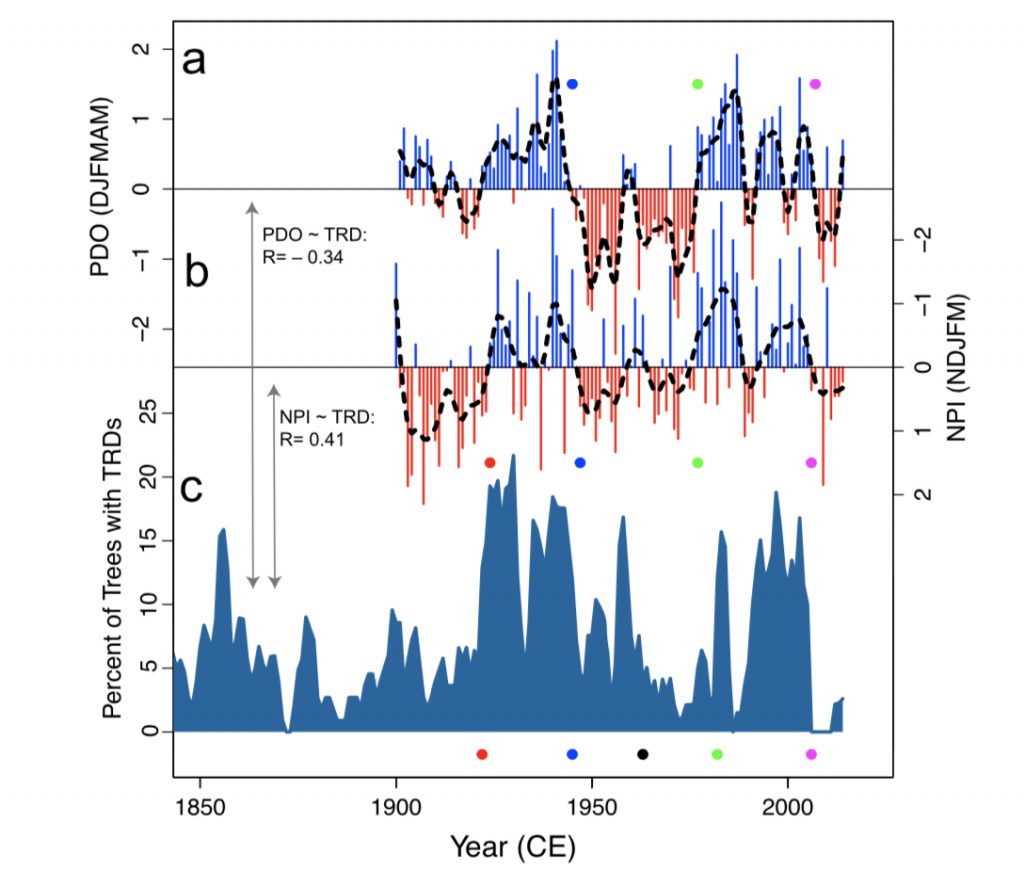

Dr. Ben Gaglioti (University of Alaska – Fairbanks) and collaborators just published another innovative study. This time Ben has assembled a time series of traumatic resin ducts (TRDs) in mountain hemlock that is a record of past winter conditions and the strength of the Aleutian Low. The article appeared in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences.

a – The clearly-stressed trees used in this study. b – Careful observations and measurements from increment cores were taken to work out the timing of maximum wind stress and storminess. c, d – Examples of Traumatic Resin Ducts in the tree rings.

Once assembled, the decadal variability of the winter time record was clearly related to the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (see below). This new record is the first of its kind and gives us a new record of wintertime variability from the North Pacific.

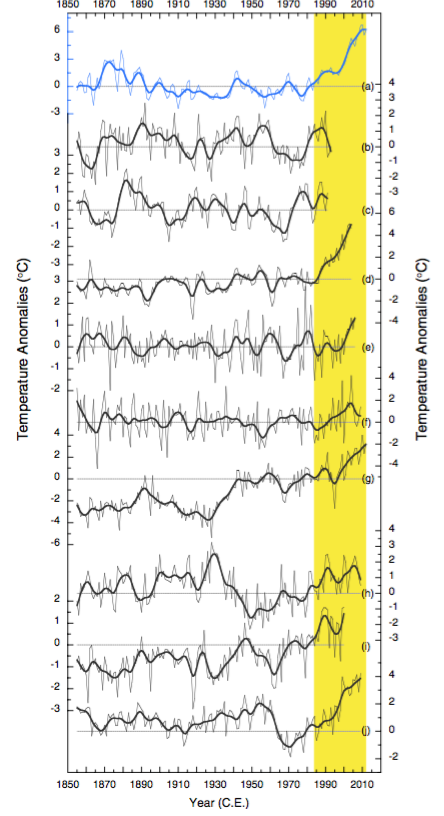

Rob Wilson (University of St. Andrews) lead a study from the Yukon. He used blue intensity tree-ring records from white spruce to improve dendroclimatic temperature reconstructions from the southern Yukon.

The study is titled: Improved dendroclimatic calibration using blue intensity in the southern Yukon. and the abstract reads like this: In north-western North America, the so-called divergence problem (DP) is expressed in tree ring width (RW) as an unstable temperature signal in recent decades. Maximum latewood density (MXD), from the same region, shows minimal evidence of DP. While MXD is a superior proxy for summer temperatures, there are very few long MXD records from North America. Latewood blue intensity (LWB) measures similar wood properties as MXD, expresses a similar climate response, is much cheaper to generate and thereby could provide the means to profoundly expand the extant network of temperature sensitive tree-ring (TR) chronologies in North America. In this study, LWB is measured from 17 white spruce sites (Picea glauca) in south-western Yukon to test whether LWB is immune to the temporal calibration instabilities observed in RW. A number of detrending methodologies are examined. The strongest calibration results for both RW and LWB are consistently returned using age-dependent spline (ADS) detrending within the signal-free (SF) framework. RW data calibrate best with June–July maximum temperatures (Tmax), explaining up to 28% variance, but all models fail validation and residual analysis. In comparison, LWB calibrates strongly (explaining 43–51% of May–August Tmax) and validates well. The reconstruction extends to 1337 CE, but uncertainties increase substantially before the early 17th century because of low replication. RW-, MXD- and LWB-based summer temperature reconstructions from the Gulf of Alaska, the Wrangell Mountains and Northern Alaska display good agreement at multi-decadal and higher frequencies, but the Yukon LWB reconstruction appears potentially limited in its expression of centennial-scale variation. While LWB improves dendroclimatic calibration, future work must focus on suitably preserved sub-fossil material to increase replication prior to 1650 CE.

The Figure above shows the location of the Yukon study site and includes various other sites the Wooster lab has worked on in Alaska. Rob has been a great help in the efforts at the Wooster Tree Ring Lab facilitating our lab’s ability to perform these analyses.

Mary Garvin (Biology, Oberlin College) lead the study using tree-rings and chemical analyses entitled: A survey of trace metal burdens in increment cores from eastern cottonwood (Populus deltoides) across a childhood cancer cluster, Sandusky County, OH, USA.

Abstract: A dendrochemical study of cottonwood trees (Populus deltoides) was conducted across a childhood cancer cluster in eastern Sandusky County (Ohio, USA). The justification for this study was that no satisfactory explanation has yet been put forward, despite extensive local surveys of aerosols, groundwater, and soil. Concentrations of eight trace metals were measured by ICP-MS in microwave-digested 5-year sections of increment cores, collected during 2012 and 2013. To determine whether the onset of the first cancer cases could be connected to an emergence of any of these contaminants, cores spanning the period 1970–2009 were taken from 51 trees of similar age, inside the cluster and in a control area to the west. The abundance of metals in cottonwood tree annual rings served as a proxy for their long-term, low-level accumulation from the same sources whereby exposure of the children may have occurred. A spatial analysis of cumulative metal burdens (lifetime accumulation in the tree) was performed to search for significant ‘hotspots’, employing a scan statistic with a mask of variable radius and center. For Cd, Cr, and Ni, circular hotspots were found that nearly coincide with the cancer cluster and are similar in size. No hotspots were found for Co, Cu, and Pb, while As and V were largely below method detection limits. Whereas our results do not implicate exposure to metals as a causative factor, we conclude that, after 1970, cottonwood trees have accumulated more Cd, Cr, and Ni, inside the childhood cancer cluster than elsewhere in Sandusky County.

Figure that shows the extent of the cancer cluster that coincides with more accumulated Cd, Cr and Ni in the tree-rings.