The fate of Alaska yellow-cedar (Callitropsis nootkatensis D. Don; Oerst. ex D.P. Little) in a changing climate is a fascinating tale. Our collaborator, Lauren Oakes published a book last year called the Canary Tree which is a story of yellow-cedar (YC) and her research. The crux of the story is that increased temperatures and loss of snow pack make fine roots of the YC more vulnerable to frost damage and, in some instances, this freezing is killing extensive stands of the tree.

Three of the students who helped sample the trees in Juneau during the summer of 2017 (photo credit: Jesse Wiles).

Three of the students who helped sample the trees in Juneau during the summer of 2017 (photo credit: Jesse Wiles).

Brian Buma, also a recent collaborator and author on our contribution, has written several articles describing the biogeography of YC decline. His work includes (Buma, 2018) the thought that with rapid enough rates of warming in Southeast Alaska, the population of YC may not be vulnerable if the warming also decreases the frost threat. This work is informed by mapping of the southern limit of the species, which is thriving in Oregon and Washington where winter temperatures are well above 0 degrees C. The leading edge of the decline is most vulnerable as the mean winter temperatures are in the range of between -2 and +2 degrees C. Our study sites in Juneau are entering this temperature range and thus are/will be impacted by warming winters and the transition from snow to rain.

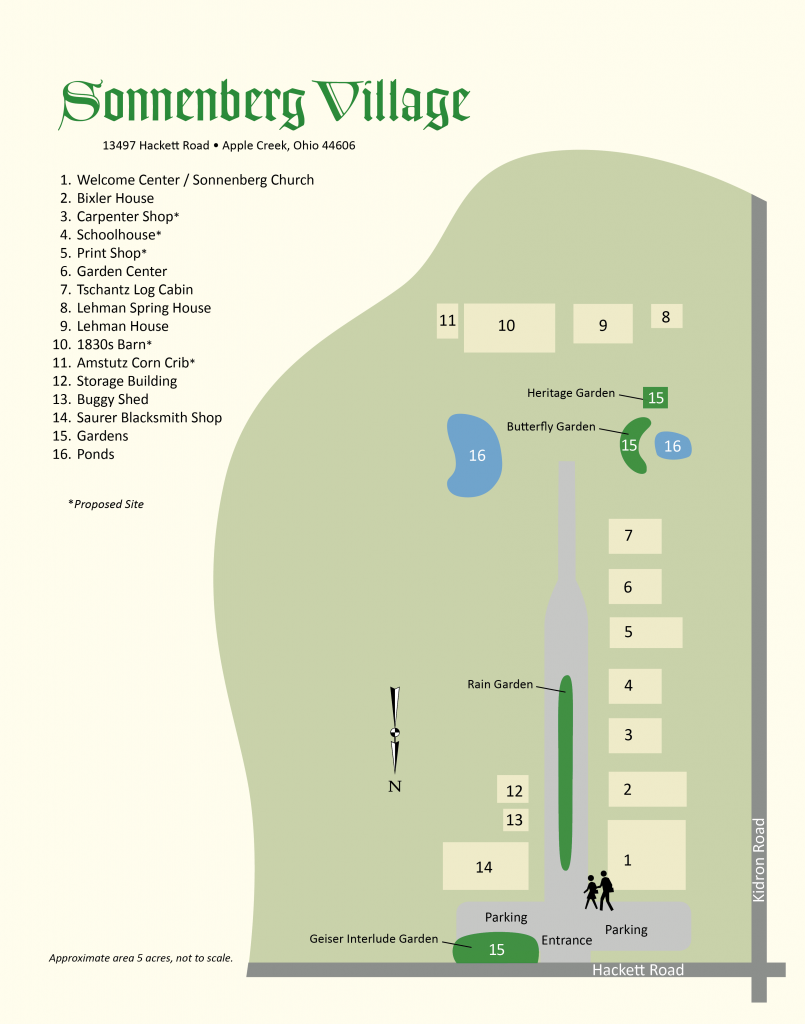

Location of study sites.

Location of study sites.

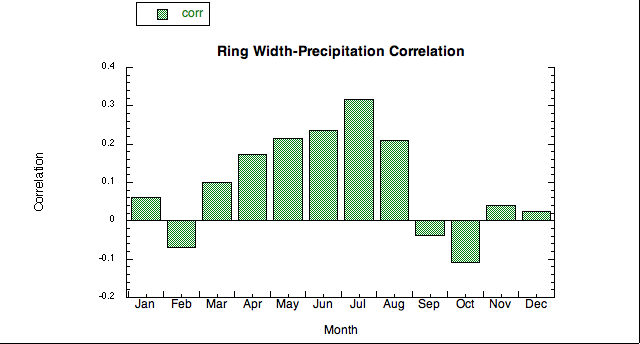

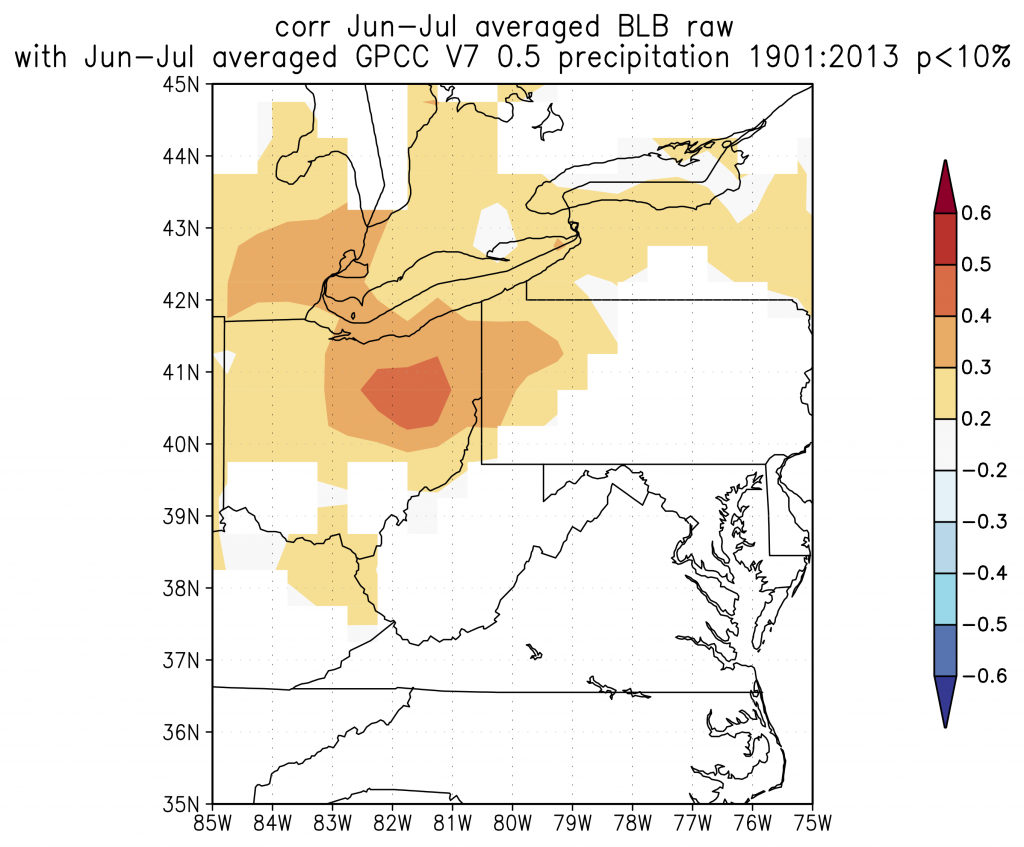

Our new paper titled:Yellow-Cedar Blue Intensity Tree Ring Chronologies as Records of Climate, Juneau, Alaska, USA appeared in the Canadian Journal of Forestry Research and describes well-replicated tree-ring chronologies made up of ring-width and latewood blue intensity measurements. Where previously YC has not been considered to be a strong candidate for reconstructing past climate, we have found that blue intensity measurements have a strong signal much stronger than ring-widths.

The Abstract of our paper is here: This is the first study to generate and analyze the climate signal in Blue Intensity (BI) tree-ring chronologies from Alaskan yellow-cedar (Callitropsis nootkatensis D. Don; Oerst. ex D.P. Little). The latewood BI chronology shows a much stronger temperature sensitivity than ring-widths (RW), and thus can provide information on past climate. The well-replicated BI chronology exhibits a positive January-August average maximum temperature signal for 1900-1975, after which it loses temperature sensitivity following the 1976/77 shift in northeast Pacific climate. This is a temporary loss of temperature sensitivity from about 1976 to 1999 that is not evident in RW or in a change in forest health but is consistent with prior work linking cedar decline to warming. The positive temperature response of BI after 1999 suggests a recovery, which remains strong for the most recent decades, although the coming years will continue to test this observation. A confounding factor is the uncertain influence of a shift in color variation from the heartwood/sapwood boundary. Future expansion of the yellow-cedar BI network and further investigation of the influence of the heartwood/sapwood transitions in the BI signal will lead to a better understanding of the utility of this species as a climate proxy.

References:

Buma, B. 2018. Transitional climate mortality: slower warming may result in increased climate-induced mortality in some systems. Ecosphere 9: e02170.

Wiles G, Charlton J, Wilson R, D’Arrigo R, Buma B, Krapek J, Gaglioti B, Wiesenberg N, Oelkers R., 2019, Yellow-cedar blue intensity tree ring chronologies as records of climate and forest-climate response, Juneau, Alaska, USA. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfr-2018-0525.